Scarica il programma! Download the program!

Scroll down for English Version

Oltre al sogno di volare, l’umanità da secoli immagina di andare sulla luna, da Luciano di Samosata II a.c. fino a Elon Musk, sebbene mossa non sempre dalle stesse ragioni.

Per Astolfo, nell’opera di Ludovico Ariosto, andare sulla luna era l’unico modo per recuperare il senno perduto di Orlando. Ma una volta sull’astro, il viaggiatore interstellare si rende conto di aver perduto anche lui parte della sua ragione. Qui infatti, si trovano ampolle con la ragione di chi in terra, per un motivo o per un altro, ha dimenticato parte di sé.

Andare sulla luna per gli americani e i russi del secolo scorso era spostare la guerra, il conflitto, la sfida, in cielo, significava dar conto di competenze e conoscenze, innovazioni tecnologiche, spingersi oltre i confini terrestri per mostrare al mondo chi era più forte. Era una questione simbolica, una lotta in cui la narrazione valeva più dell’esserci stati veramente. In effetti, se ci sia stato un uomo o meno sulla luna è di minor valore rispetto alla narrazione che se ne è fatta. Se effettivamente si trattasse di un film di Orson Welles, sarebbe sicuramente un film sublime.

Per Elon Musk, e altri imprenditori multimilionari, andare sulla luna e portare persone nello spazio, è un business. Forse non dovrebbe stupirci: in fin dei conti sono eredi della storia che gli ha preceduti: da una parte la voglia bambinesca di questi signori di andare sulla luna, un capriccio che si possono permettere, dall’altra aprire un altro mondo, renderlo accessibile, trasformarlo in un altro bene di consumo.

“Eppure la luna non è di nessuno, e nessuno la può comperare”. I trattati internazionali la definiscono come “patrimonio comune dell’umanità dove sono bandite, oltre alle armi, qualunque forma di appropriazione nazionale o rivendicazione di sovranità, nonché l’esercizio della proprietà privata”. E speriamo di non dover tornare su queste parole, di non dovere mettere in dubbio la proprietà della luna, rendendola soltanto un’altra terra di conquista.

Talvolta, la vista si appanna quando si guarda troppo questo astro, soprattutto nelle notti di luna piena; lunatici, lunatiche, streghe, stregoni, lupi mannari e altri esseri bizzarri, anormali, gente che crede che tutto l’universo sia pieno di Dio, e che l’universo sia infinito, che la nostra terra, la nostra luna, il nostro sole, siano solo una piccolissima parte del cosmo, è finita emarginata, condannata, additata come eretica o pazza. Eppure oggi parliamo di multiversi in fisica!

Le lunatiche e le streghe, troppe sono state rinchiuse o bruciate. In una divisione manichea, che troppo spesso sembra l’unica possibile, l’umanità ha sempre visto nel “Buio” il male e nella “Luce” il bene.

Il popolo della luna, il popolo della notte, il popolo del senno perduto, quello della rugiada mattutina, chissà che non sia proprio quello che ci risveglia dal sonno del giorno, dagli affanni, dalla fatica, dalla dimenticanza. Chissà se quel popolo, nel sogno, non suggerisca alla scienza nuovi strumenti di ricerca e a noi nuove forme di vita inoperosa, in cui sia possibile con una poesia comprare un caffé. Poiché la luce del sole rende tutto visibile tanto da accecarci per la sua abbondanza, la luce della luna invece riflette, soppesa, illumina poche cose, ma in profondità.

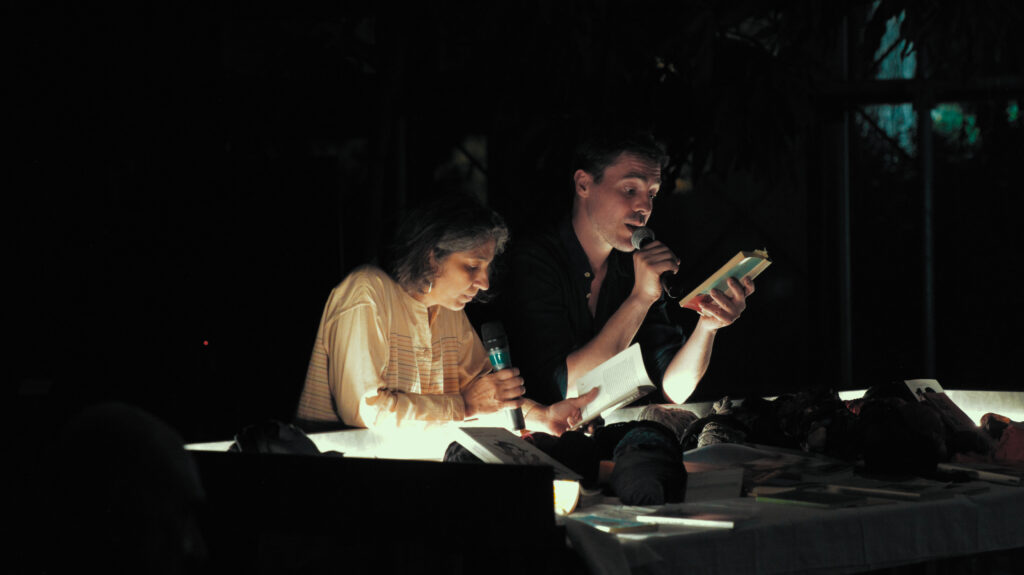

Raccolta di idee, suggestioni e contributi di Irene Panzani, curatrice di GIUNGLA, a seguito del gruppo di discussione che si è tenuto presso la Biblioteca Civica Agorà di Lucca nel mese di maggio 2022. Grazie a tutte le partecipanti ed i partecipanti!

La notte è anche un sole

ENGLISH

In addition to the dream of flying, mankind has been imagining going to the moon for centuries, from Lucian of Samosata II B.C. to Elon Musk, although not always motivated by the same reasons.

For Astolfo, in Ludovico Ariosto’s opera, going to the moon was the only way to recover Orlando’s lost wits. But once on the star, the interstellar traveller realises that he too has lost part of his reason. Here, in fact, are found ampoules with the reason of those on earth who, for one reason or another, have forgotten part of themselves.

To go to the moon for the Americans and Russians of the last century was to move the war, the conflict, the challenge, to the sky, it was to account for skills and knowledge, technological innovations, to go beyond the earth’s borders to show the world who was stronger. It was symbolic, a struggle in which the narrative was worth more than actually being there. In fact, whether or not there was a man on the moon is of less value than the narrative of it. If it were actually an Orson Welles film, it would certainly be a sublime film.

For Elon Musk, and other multi-millionaire entrepreneurs, going to the moon and getting people into space is a business. Perhaps this should not surprise us: after all, they are heirs to the history that preceded them: on the one hand the childish desire of these gentlemen to go to the moon, a whim they can afford, on the other hand opening up another world, making it accessible, turning it into another consumer good.

“Yet the moon belongs to no one, and no one can buy it”. International treaties define it as ‘the common heritage of mankind where any form of national appropriation or claim to sovereignty, as well as the exercise of private ownership, is prohibited, in addition to arms’. And let us hope that we do not have to go back on these words, that we do not have to question the ownership of the moon, making it just another land of conquest.

Sometimes, one’s vision gets blurred when one looks too much at this star, especially on nights when the moon is full; lunatics, moodies, witches, wizards, werewolves and other bizarre, abnormal beings, people who believe that the whole universe is full of God, and that the universe is infinite, that our earth, our moon, our sun, are only a tiny part of the cosmos, have ended up marginalized, condemned, singled out as heretics or madmen. Yet today we speak of the multiverse in physics!

Lunatics and witches, too many have been locked up or burnt. In a Manichean division, which all too often seems the only one possible, humanity has always seen the ‘Dark’ as evil and the ‘Light’ as good.

The people of the moon, the people of the night, the people of lost wits, the people of the morning dew, who knows if it is not precisely that which awakens us from the sleep of the day, from fatigue, from forgetfulness. Who knows if that people, in the dream, does not suggest to science new instruments of research and to us new forms of idle life, in which it is possible with a poem to buy a coffee. Since the light of the sun makes everything visible to the point of blinding us by its abundance, the light of the moon, on the other hand, reflects, weighs, illuminates few things, but in depth.

Collection of ideas, suggestions and contributions by Irene Panzani, editor of GIUNGLA, following the discussion group held at the Agorà Civic Library in Lucca in May 2022. Thank you to all the participants!